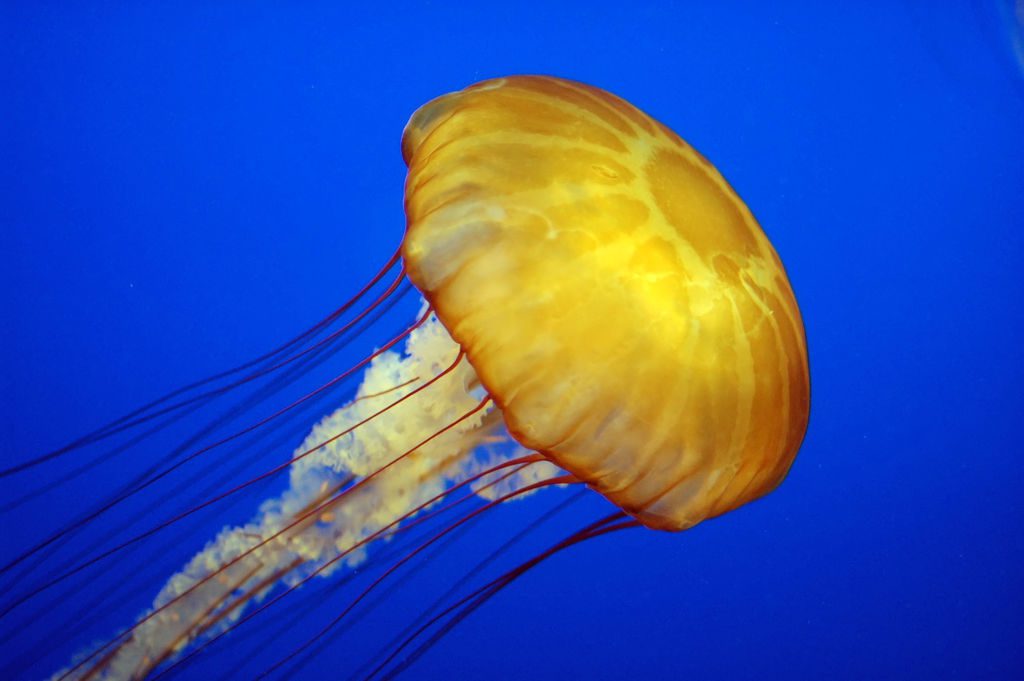

SUMMER is the jellyfish season, a time to be wary of a serious jellyfish sting.

It is unfortunate that most people are only aware of the dangers of a few jellyfish and completely unaware of how these creatures are really quite amazing.

Despite having no brains, no heart and no blood, jellyfish have survived for more than 500 million years – even pre-dating dinosaurs (bet you didn’t know that!).

There are more than 100 species of jellyfish that have been recorded along the Great Barrier Reef, including the infamous box jellyfish and Irukandji jellyfish.

The slightly less infamous blue bottle is technically not a true jellyfish.

Here are some less than relevant but fun facts about jellyfish.

· Jellyfish are not actually fish. They are gelatinous zooplankton (or invertebrates from the phylum Cnidaria).

· Their bodies are made up of as much as 98 per cent water – the ultimate camouflage for a marine creature.

· They might not have a brain or heart, but some jellyfish can see. For instance, the box jellyfish has 24 ‘eyes’, two of which can see in colour.

· Jellyfish rely on specialised gravity-sensitive calcium crystals to orient themselves. NASA have actually sent jellyfish to space, in the early 1990s, to study them in a zero-gravity environment.

· A group of jellyfish is not a school or a pod. It is usually called a bloom or swarm.

Here are some slightly more relevant facts about jellyfish.

· A few jellyfish species are luminescent. That can be traced to special proteins that are used as light markers in medical research, for instance, to make cancer cells visible under a microscope.

· Current research indicates that cartilage damage may be repaired with the help of collagen found in jellyfish.

· Jellyfish are an important food source for many marine animals, including sea turtles, whales, fish, sea birds and other invertebrates.

· Jellyfish is a sustainable food source that is eaten in some parts of Asia. It is high in protein and collagen, and low in calories and fat.

Here are some very relevant facts about jellyfish.

The Box Jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri), named for their body shape, have long tentacles covered with nematocysts – tiny darts loaded with poison.

People unfortunate enough to be injected with this poison may experience severe pain, paralysis, cardiac arrest and even death.

Box Jellyfish have traits that set them apart from other jellyfish.

Most notably, Box Jellyfish can swim—at maximum speeds approaching four knots—whereas most species of jellyfish float wherever the current takes them, with little control over their direction.

At only 1 – 2cm in diameter, the Irukandji Jellyfish may be the smallest jellyfish in the world but its tiny size does not take away from its dangerous sting.

While the sting itself can be mild, the symptoms – referred to as Irukandji Syndrome – can be life-threatening, however, this is only in very rare cases.

Symptoms can take between 5 – 45 minutes to develop, after being stung, and include lower backache, overall body pain, muscular cramps, chest and abdomen pain, nausea, vomiting and breathing difficulties.

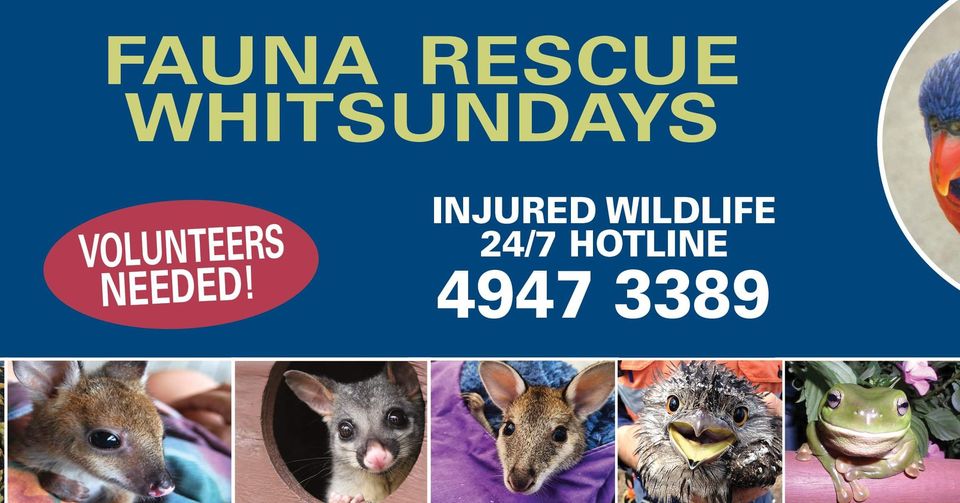

The best medicine for a serious jellyfish sting is prevention. Along the Great Barrier Reef coast, we have a ‘jellyfish season’, which roughly coincides with summer.

The risk of a serious sting is highest between October and April. The risk increases near shore, particularly for the Box Jellyfish.

Irukandji stings occur around the islands and even as far offshore as the outer reef.

Stinger nets provide some protection, but Irukandji stings have occurred in the net enclosure.

Wearing a full body Lycra suit or ‘stinger’ suit is the best protection for in-water activities.

With the right precautions, we can respect and enjoy these amazing and important creatures.