By Whitsunday Conservation Council

EACH YEAR, around the full moon in November and/or December, the world’s largest synchronised coral spawning event happens along the Great Barrier Reef, just off the Whitsundays coast.

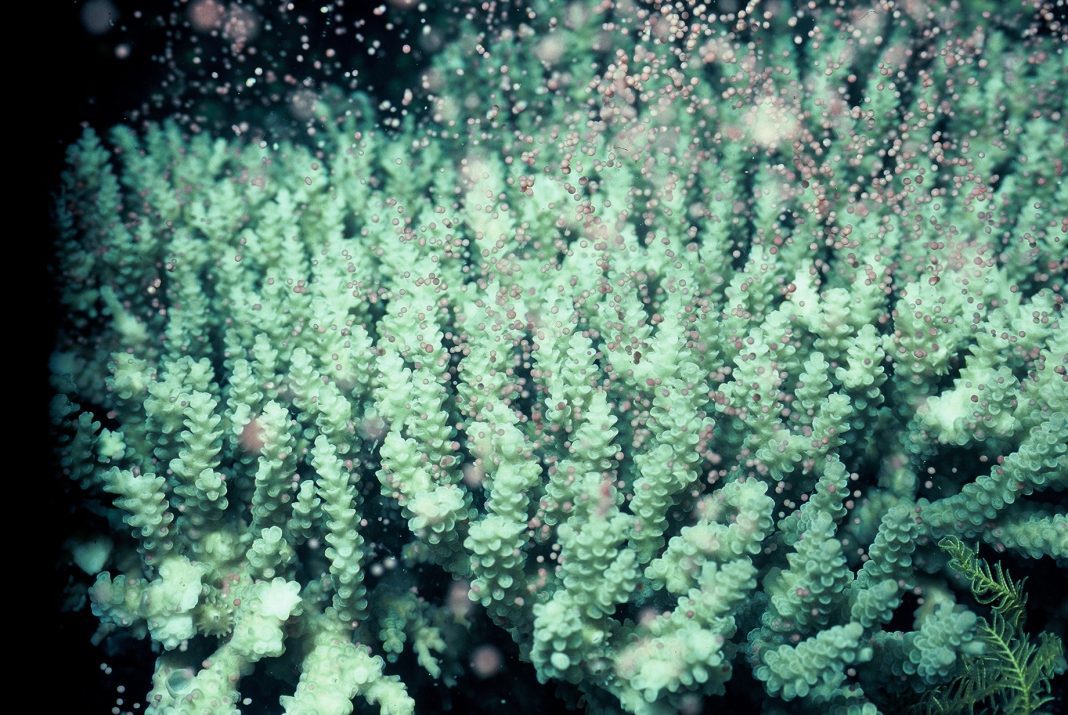

Coral reefs simultaneously release their tiny eggs and sperm into the ocean, with billions of tiny white and coloured eggs drifting towards the surface of the water, just like a ‘snowstorm’.

In ways that scientists still do not fully understand, mature corals release their eggs and sperm all at the same time.

On cues from the lunar cycle and the water temperature, entire colonies of coral reefs simultaneously release their tiny eggs and sperm into the ocean.

The synchrony is crucial, because the eggs and sperm of most coral species are viable for only a few hours. The ‘snowstorm’ makes it more likely that fertilization will occur.

The fertilized egg, known as a planula, floats in the ocean – some float for days and some for weeks – before dropping to the ocean floor.

Then, depending on seafloor conditions, the planulae may attach to the substrate and grow into a new coral colony at about 1cm a year.

Scientists have become adept at predicting the timing of the Great Coral Spawn, but there is still some guesswork and luck involved.

There are several environmental factors that affect when coral is likely to spawn, including that the ocean temperatures must be 26 degrees or above for the month before, for the eggs to mature enough.

The coral will reproduce three to six nights after the full moon in November and/or December when there’s less tidal movement.

Spawning is also most likely to take place at least three hours after sunset, when all plankton feeders are sleeping, giving eggs a higher chance of survival.

This most important reproductive event ensures the future of coral reefs but it comes with an important caveat: Corals will only reproduce if they are healthy.

If they are bombarded by stressors such as a marine heatwave (coral bleaching), poor water quality, or overfishing, their energy will be directed at survival, instead of reproduction.

To ensure the future of coral reefs, we must keep corals healthy and resilient.

Story contributed by Whitsunday Conservation Council.